Domino (part two)

The evolution of modern warfare will leave an indelible mark... on the whole world

The following series of three articles will focus on the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its geopolitical consequences by offering a comprehensive forecast in the latest publication.

For a better understanding of the content, it may help to read the previous in-depth article.

The first is a brief description of the evolution of the conflict from the outbreak to the retreat from Kiev and northern Ukraine.

The second focuses briefly on the consequences that this war will have on the world chessboard in terms of economics, geopolitics and the balance of powers and then reconnects to Ukraine's prospects.

The third will return to the themes of the second by delving deeper and concluding the outlook with an eye on Russia.

Good reading.

Fragmentation, insurgency and vanished stability

So, which could and will be the consequences of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine?

But, above all, what evolutions and trends in history will be reinforced by the war?

The first is the risk of a fragmentation of the Russian economy leading to new centrifugal drives inside the Federation.

The second is the transformation of part of Ukraine into a no man's land with the consequent emergence of new criminal networks and an immediate evolution of the black market in arms towards the resale of advanced technology.

There is also an erroneous tendency to place the emphasis solely on the country's weight in the supply of food and other raw materials to the second and third world or 'emerging markets'. However, the impact will also be felt in the production of microchips, cars, household appliances, energy supplies and perhaps other sectors not immediately visible in the Old Continent itself.

The third is a strong push towards the devolution of armed conflicts in the direction of a more clandestine, devious, violent, hyper-technological form where it will be difficult to guarantee respect of the rules and consensus defined during centuries of European hegemony. In other words, war will have a face that will be increasingly distant from the one that has been shaped over the last four centuries of history (we briefly touched on this subject in 'The New Face of War/Part 1').

At the same time, an additional element may emerge in the coming decades that is already part of many armed forces renewal strategies around the world but with a more limited emphasis.

In the face of a decreasingly young population, in many European and Asian countries, the automation of many of the logistics and resupply activities of the troops takes on a whole new importance in order to promote the replenishment of the infantry.

Fourth are the consequences for the global economy. These affect not only Europe and Russia but also the other BRICS (India, China, South Africa, Brazil) and probably also the United States. Through each of them, the rest of the world will also be affected. It remains to be seen what the fallout might be on the West and the rest of the world economy.

Additionally, any crisis situation at the regional level could then cause a concatenation of events affecting the other three points just mentioned.

Wanting to outline a less vague analysis in spite of the general uncertainty, we would say that the regionalisation of the international economy will at this point be accompanied by rapid ruptures in the production and distribution chains. These were already a possibility at the beginning of the pandemic, but it still seemed possible to manage the process of industrial re-entry. At this point, the damage that the sanctions regime could cause to European economies, with the blockade of the Ukrainian economy (which is extremely important for raw materials) and Russian difficulties in guaranteeing its exports, will lead to widespread dysfunctionality in the international supply system. In short, the individual regional economic blocs will have to reorganise themselves and hunt for resources by buying them from a neighbouring or trusted supplier to ensure their most profitable industrial base can function properly.

The rest of the economy will have to live with the turbulence as states try to restructure their public debts and manage inflation rates, keeping them manageable between 5% and 20% (effectively defined as 'galloping inflation') but with the latent risk of seeing it spill over into hyperinflation (similar to Germany in 1929), also as a result of the future collapse of the respectability of the Central Banks.

This article will focus mainly on the first three points and in particular on the impact of the war on Ukrainian territory and the kind of influence this will have on the Russian cultural sphere. The third will reconnect the issues addressed in the first two with the economic impact to highlight the relationships most relevant to the prospects of Russia and the rest of the world.

Having said that, we would immediately start by saying that the huge mountain of nonsense (that was not the first word we used) that the newspapers are peddling about the prospects of the Russian economy is to be taken and thrown in the bin.

The current sanctions regime is insufficient by its very nature to stifle Russian economic activity.

Let us also clarify that we are not suggesting tightening it given that the systemic risk to the entire global economy, already outlined in "To Russia the burden of decision", is more than concrete with the current retaliatory measures.

As already mentioned in the first point, the strategy pursued by Washington is one of "numbing down" the Bear economy through targeted sanctions to hit Moscow's ability to maintain the post-Soviet financial scaffolding and the Bank of Russia's control over the activities of individual states within the Federation.

This could be achieved by blocking or slowing down foreign debt payments and capturing the flow of international hard currency (Euros, Yen, Pounds Sterling, Dollars) and precious metals (Gold, Silver, Platinum but also copper to starve the country of resources needed for industry). Washington is aware of Russia's almost dominant position in the markets for these resources but aims to make trade difficult so as to slow everything down. Boycotts and secondary sanctions have worked and should work for a while longer as inhibitors to Moscow's ability to position itself in international markets.

All this leads to a process of 'slow atomisation', not only because the exchange of goods becomes difficult, but because by affecting monetary flows, the state has to cope with debt payments on the domestic market with its own reserves (guaranteeing liquidity and elasticity to the private debt markets in order to avoid systemic risks) without a clear prospect on a return to normalcy, and then having to deal with the impact of the atrophy of various sectors of the economy with the blockage of trade where the sanctions regime bites hardest.

The second phase in particular is likely to see the Russian Central Bank pursue a series of fiscal stimuli combined with public subsidy measures with the aim of boosting the economy as soon as the first signs of stabilisation and recovery arrive.

However, it is not obvious that the measures will be sufficient to ensure a smooth restart. The combined impact of the flight of Western and non-Western companies (for fear of secondary sanctions) coupled with the blockade of foreign currency flows and the attack on logistics networks through the mass boycott (again as a result of secondary sanctions many ports and transport activities refused, almost all of them until a few months ago, to cooperate with the Russian authorities. This is very evident in connection with the transport of oil and derivatives to Asia) will force Moscow and Russian multinationals to quickly set up parallel coordination and payment systems as alternatives to the Western ones.

The final question is whether, once the sanctions have been circumvented, the additional costs can be borne for long periods by all affected regions inside the Russian Federation. The dilemma, which the Kremlin understands very well and has been working on since the collapse of the Soviet Union, becomes securing economic relief where the situation is reaching the point of no return.

If in fact modern finance allows effective management of the money supply thanks to electronic payment systems, it is precisely centralist functionalism combined with the complexity of digital markets that creates the preconditions for dangerous slip-ups that if left to their own devices lead to unrecoverable situations.

Translated, the evolution of contemporary economies towards forms of centralism close to the most important cities for business has created imbalances in the framework of states that impoverish vast regions in favour of a much smaller number of territories.

This management is sustainable as long as individual specialised areas (New York Tri-state area, the Volga Basin, the North China Plain....) are responsive in terms of industrial production and do not create problems for the flow of international trade. However, the moment delays and logistical chains reach a breaking point (a process that had already begun at the end of the first year of the pandemic), it becomes much more complex to keep entire sectors of the economy alive because suddenly the most basic primary resources are not available.

With costs being cut to the bone, in fact, many of the elements that define international trade are based on economic logic that aims at extreme savings in terms of cash flow for companies. Left uncovered for more than two years, some multinationals have stockpiled according to the logic of 'Just in case' (warehouses and inventories with resources for a few months/few years of production) and not according to the prevailing pre-pandemic mode of 'Just in time' (no stockpiles. almost everything paid for at the time so as to have cash flows always in the positive without worrying about the risk of a disruption in the production of commodities). However, inventories are of and for the large corporations that have the revenue to secure the inflated costs of transport and warehousing.

The result is the unexpected collapse of activities that are minor in economic terms but extremely relevant for the sustainability of those territories abandoned by functionalism and globalisation.

This brings us to the third topic.

At this point, more than one country on the world stage will have a serious interest in expanding their automation technologies so that they can restart local production without too much extra cost and, in the absence of a domestic industry, will end up collaborating with someone else or acquiring the most affordable offer.

The Russians, as well as many other countries including the US, have already started automating their agricultural and military sectors using so-called 'Dual Use' technologies.

If, however, the results seem to be promising for some of the typical farming jobs, the same cannot yet be said for... almost everything else.

To date, most of the available means are relatively rudimentary missiles, ordnance or vehicles and the artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and machine learning systems that should take care of capabilities such as JDAC2, Cross Domain Deterrence, C4ISR, etc. are not yet fully implemented by the US itself.

Thus, an element comes into play whose influence is difficult to predict: the human element.

What will the private sector do and how quickly and effectively will various actors (not only companies and corporations but also private citizens) integrate complex and previously unconnected systems into a very dangerous mix of capabilities when used in a coordinated manner?

First we should roughly separate technological development into three categories shaped by the type of use for which they are intended.

States develop integrated warfare technologies with advanced software, artificial intelligence and mechanised vehicles with a set of specific objectives often defined by armed forces officers in a circumscribed manner and with predefined ends.

These include: a better view of the battlefield through the sharing of data, the development of automated parachutable veichles for supporting troops on the ground, the use of autonomous boats for mine-laying and coastal monitoring, and the modularity of armed ships, tanks and ground drones to be used for reconnaissance and surveillance.

What most characterises this type of automation is the delimited and controlled sphere in which it evolves, thus guaranteeing marked forms of supervision.

The second category of technologies is that developed by multinationals and corporations. We would like to emphasise that these are likely to be the ones pushing research and development on an ongoing basis and not the institutions.

In fact, states generally pay the initial adoption cost (often military) and then facilitate further development in the context of the private sector by guaranteeing a profit on an improvable tool.

Here already the situation changes dramatically with the use that these organisations will make of highly sophisticated tools that form the backbone of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

If used in a circumscribed manner, as we believe will happen in the majority of cases, we will see phenomena such as guerrilla warfare, industrial espionage at unprecedented levels, war for resources, in and for emerging and non-emerging markets. Additionally, and especially if a conglomerate of several corporations with dominant positions in several sectors of the economy were to emerge, the possibility of a clash between the states themselves and the private sector could re-emerge.

This was a trend that we had hoped could be contained but the refusal of European states to come to a lasting understanding with the Trump administration on a number of fronts has now led to an all too extensive degradation of the chessboard.

At this point, the reality will be one in which the states themselves will use mercenary groups to avoid relying on their troops for reasons ranging from mistrust twoards their own army, lack of resources to even open incompetence in handling the situation (the Wagner group is not an expression of this trend).

It may sound ridiculous but in reality in nations that possess sufficient liquidity but a population that childishly rejects any aspect of warfare (including self-defence) the best choice will end up being that of a private, professional and expendable group.

Finally, the third category is probably the one that will most define and be shaped by the human element, i.e. the unexpected.

This will basically be the union of all those groups and individuals who will develop and make their research/products/software, artificial intelligence, machine learning or other tools available to all.

Examples of this trend have already been seen in relation to weapons created with 3D printers where graphic designers and industry enthusiasts from all over the world have collaborated to create and or improve small-calibre designs that later reappeared in various conflicts around the world including the civil war in Myanmar.

The same principle will quietly be applied to many other sectors, creating autonomously disseminated technologies that are difficult for governments to control.

This last phenomenon more than any other should have alerted the governments of the world before pushing so blatantly for the promotion of digital currencies issued by central banks.

By now it is too late to save face (not to take a step backwards). Another question entirely is whether this type of instrument succeeds in taking the dominant position that states believe it can.

These three different groups will shape future technological evolution in a degraded global institutional environment with high levels of distrust on the part of populations.

We will expand on what was said in the last article.

The Prussian general and military theorist Carl Von Clausewitz said: 'No one starts a war -or rather, no one in his right mind should- without first having a clear idea of what he intends to get out of it and how he intends to conduct it' ('Vom Krieg/On war' 1832).

Almost one thousand nine hundred years earlier, the Roman historian Tacitus had the leader of a Pictish tribe in present-day Scotland, Caledon, utter the following words about the Romans: 'Ubi solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant' or 'Where they make the desert, they call it peace' ('Agricola' 98 AD).

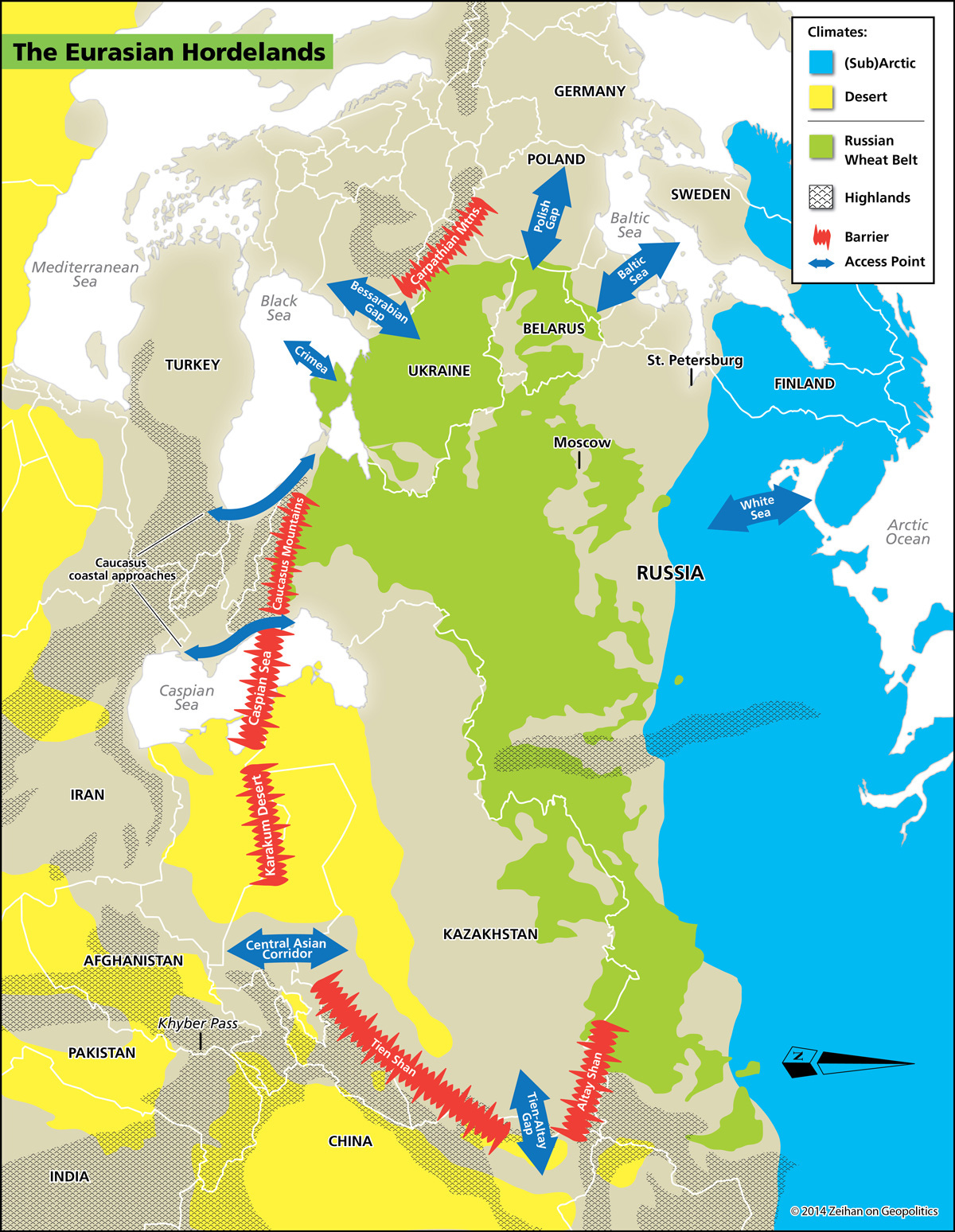

Taking these two quotes and putting them together gives more or less an idea of the Kremlin's plan for Ukraine, which, to varying degrees, could also involve all those territories that have historically been part of Russia's direct sphere of influence (to be distinguished from the Soviet satellite states).

The transformation of Ukraine into a failed state is probably inevitable given the damage caused by the war to its infrastructure and population. Estimates by the Ukrainian government are around 550 billion ($) while those of the World Bank and IMF are around 60 billion (definitely downwards although the estimate only includes infrastructure damage).

Ignoring the figures for an economy whose currency, the hryvnia, is weak in relation to sterling, the dollar and the euro, the difficult dimension that Kiev would have to face becomes clearer if one takes into account the damage suffered by the agricultural and industrial sectors.

In the second sector, at least a large part of the southernmost belt of the country (including the Donbass) will end up in Russian hands, making trade much more difficult in the absence of fuel supplies for ships and transport to the hinterland particularly around Odessa and Mykolayev. Should the Kremlin succeed in securing control of all sea outlets the Ukrainian economy would simply be crushed by having to rely on the rest of Europe for the majority of trade and no longer having the same relevance in the Black Sea and Mediterranean region. Further, the takeover of the Donbass, already a heavy blow in itself as at its pre-2014 peak it is estimated to have produced almost 12% if not 20% of GDP and ensured 1/4 of exports, will hit the ability of industries in the centre of the country to operate at all-time full capacity quite heavily.

Putting together the loss of territories of high strategic and economic importance with the loss of agricultural equipment, the failure of planting in much of the country (government estimates indicate a 20% drop in the harvest but it will almost certainly be much greater), the placement of mines, the absence of fuel and other factors at least 30% of the country's economy is and will remain stranded for at least a couple of years (some suggest 55%).

As if this were not enough, it is now clear that Ukrainian humanitarian corridors are being directed towards Russia in the conquered territories, that many agricultural vehicles are being destroyed or confiscated, that the entire south-east of the country may be absorbed by the denomination of economic flows in roubles, and that missile attacks on refineries, spare parts factories, bridges, and the railway network are continuing.

To conclude by joining the first and second points together the result will be a probable (AHEM...further) widespread economic depression in the Black Sea region with impacts on the food security of almost all emerging markets, setting the stage for various insurgencies but above all for widespread insecurity throughout European Russia (rumours suggest that some sabotage in Russia is the first sign of this).

Nevertheless, Moscow may be able to push an important slice of activity in the west of Ukraine towards itself (as it has already done in Donbass and Crimea) due to the presence of still intact infrastructure and cultural proximity.

The Russians' ability to redefine geographical maps by manipulating local populations towards absorption is renowned and can be traced back to the very birth of their ethnic group. This is also a trait common to many of the nations that control the region in which they are located.